Introduction and Usage

躺平 (tǎng píng) translated directly means to lie flat. For example, the sentence “幫病人躺平” translates to “help the patient lie [down] flat”. In recent years, this term has become very popular among Chinese netizens. 躺平 has adopted a new meaning among youth in China; to just lay back, do nothing, and remove themselves from the pressures of society. The term 躺平 gained popularity among Chinese internet users starting around 2021. The term quickly blew up, with many internet users creating groups to talk about the 躺平 lifestyle and many people began to sell merchandise with the term on it. However, the term was quickly criticized by the Chinese government, and many groups on social networking sites relating to 躺平 were removed. Critics of the 躺平 movement in China has labelled people that use this term as “lazy”.

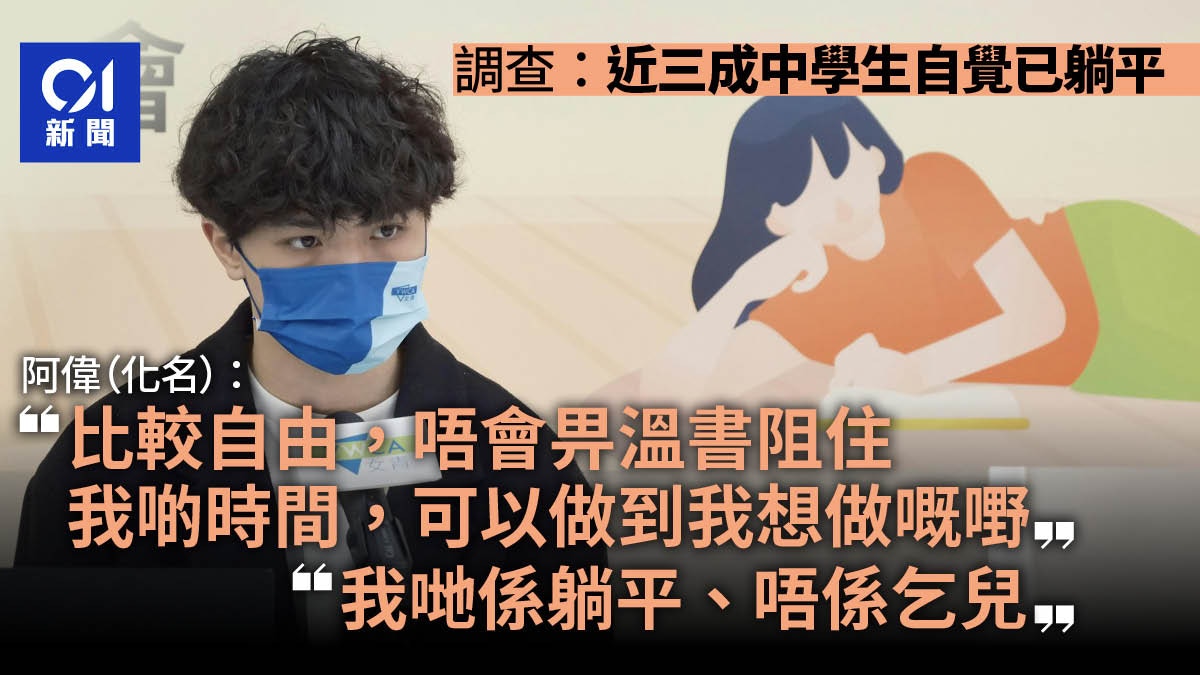

“It’s more free, you aren’t limited to what you study. My time can be used for what I want to do.”

“We are 躺平, not beggars.”

Contemporary Work Culture

The Concept of the Iron Rice Bowl (鐵飯碗)

To understand contemporary Chinese work culture, it is important to explore the idea of the 鐵飯碗, or iron rice bowl. When the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was first established, 毛澤東 (Mao ZeDong) used a planned economy for the nation. In this economy, people would be assigned jobs by the government. These jobs would include lifelong employment as well as other benefits such as healthcare. Essentially, the freedom of choice was sacrificed for job stability. This was a very stable employment, and thus coined the term 鐵飯碗. This system would continue for about 50 years until 鄧小平’s (Deng XiaoPing) period of reformation and opening up (改革開放). During this period, the Chinese economy shifted towards a market economy, and many state-owned enterprises would be privatized. This caused mass layoffs (下崗) in China; about 34 million workers were laid off between 1995-2001, and the unemployment rate reached to more than 10% (about the same as the 2008 Great Recession). This was known as the breaking of the iron rice bowl (打破鐵飯碗). Following these mass layoffs, many struggled to find new employment for various reasons such as age and lack of experience. Additionally, these mass layoffs were very sudden unexpected. Since the 鐵飯碗 jobs were thought to be very stable, many people were not prepared, and few people had savings.

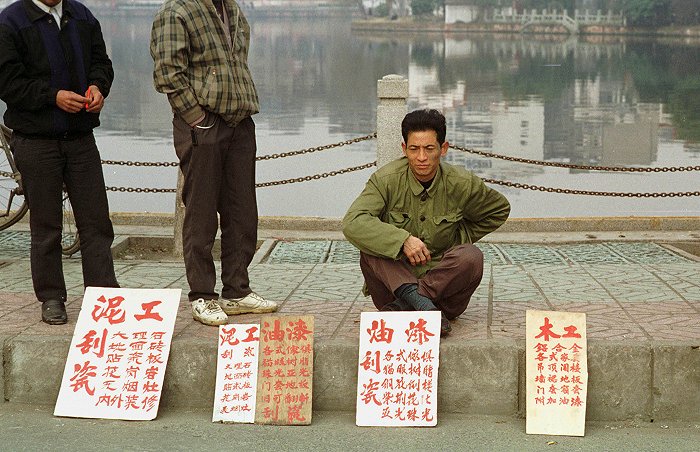

A man on the side of the road looking for work in 1998.

These mass layoffs were very recent in Chinese history, and it still lives in the consciousness of many working adults in China today. As a result, it created a kind of trauma within Chinese society with many working people today working more and for longer hours in case of another mass layoff.

The 996 and 007 Work Schedules

Headline: Overworked for a year and gained 20kg;

Helpless woman: Young girl turned into a fat auntie

In the United States, the most common work schedule is the 9 to 5, or 9:00am to 5:00pm for 5 days a week. In China, the work week is almost doubled under the 996 work schedule (996工作制度). This work schedule refers to working from 9:00am to 9:00pm for 6 days a week. Additionally, many people also work overtime (加班) on top of the 996 work schedule. In recent years, a new work schedule has arisen: 007. This work schedule refers to working 24 hours, 7 days a week. This kind of work schedule is very unhealthy both physically and mentally to works with many experience burn out after a few years.

The video below by VICE Asia gives a lot of insight into the 996 work culture in China.

It is important to note that there is a labor surplus in China, meaning that there are not enough jobs for the population. This labor surplus creates an environment where many workers feel that they can be replaced easily. This also creates a “rat race” where people are constantly competing with each other by working more and more. Considering the job insecurity faced by the people during the breaking of the iron rice bowl, it is easy to understand why many people continue to work under these conditions. In their minds, they do not have another option.

A career fair at Tsinghua University (清華大學), one of the top universities in China.

White Collar vs Blue Collar

For many Chinese, there is a hierarchy in what job you have: white collar jobs (白領工作) are usually seen as having a higher status than blue collar jobs (藍領工作). However, a recent phenomenon is flipping this hierarchy on its head. Many Chinese youth are fed up with the stressful life of white-collar work and have turned to an alternative: blue-collar work. Despite being “lower” in the job hierarchy, many youth find blue-collar work liberating as there is not as much competition and the ability to choose their own working hours.

Significance

躺平 reflects a growing disdain for the toxic work culture that exists, and a growing resistance against the exploitation of workers in China. While 躺平 is most directly related to the work culture in China, it is also shows the rejection of societal pressures in China as a whole such as getting married, having children, and owning a home. The term 躺平 may just translate to lie down, but to many youth in China, it embodies the struggles and resistance against involution found in the work culture found in contemporary China.