1951 Unequal Access

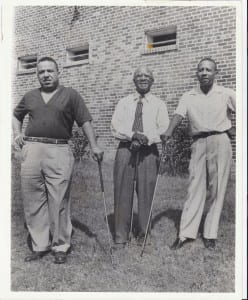

1951 Atlanta Golf Committee

The Atlanta Golf Committee was formed to combat segregation of public golf courses after the foursome was denied play at Bobby Jones. The group grew to over 300 members, and was represented by attorneys R.E. Thomas, E.E. Moore, Jr., and S.S. Robinson. They wrote letters in an attempt to negotiate with the Municipal Parks and Airport Committee regarding the city’s code banning African Americans from public parks. Although a series of letters were sent, their requests were never considered.

1953 Taking Action

1954 McHale and the KKK’s Motion to Dismiss

1954 Separate but Equal

1955 Appealing to the Supreme Court

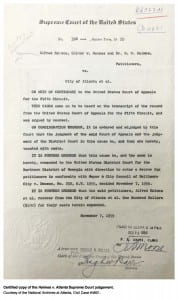

After Judge Sloan ruled “separate but equal” was applicable to golf facilities, the NAACP became involved in the case. Mr. John H. Calhoun, president of the Atlanta NAACP and attorneys from the national office joined the case on appeal, including Jack Greenberg, Robert L. Carter and Thurgood Marshall, who would later serve on the US Supreme Court. The case was carried to the US Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit in New Orleans, Louisiana. A decision was rendered on June 17, 1955, which asserted the lower court had offered the necessary restitution. The legal team decided to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Law of the Land