In class, we had the option of wearing an Ivy outfit to earn extra points. While I thought I did not have any Ivy clothes, at least at the beginning of the semester, I now have a fuller understanding of what Ivy is that allowed me to piece together an appropriate outfit. In this response, I will show how my clothing, piece by piece, derives from the Ivy style so that the reader can too understand the connections between Ivy and a variety of clothes.

The Shoes

The shoes I picked are a navy-blue pair of vans, a type of sneakers. Sneakers have there history rooted in athletics; some of the first sneakers were marketed for basketball. This athletic-yet-fashionable shoe could easily have been picked up by Princeton students in the early 1930s, whose casual/athletic wear was the origin of Ivy. After all, as Truefelman puts it, “A lot of preppy clothes started as sportswear (What is Democracy 00:16:26-00:16:32).”

The way sneakers were manufactured also played an important role in them becoming Ivy clothes. As fashion historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell put it, “the sneaker became one of the most democratized forms of footwear(Crisman-Campbell par. 7)” in part due to their ability to be mass manufactured. This parallels the origins of Ivy in Brooks Brothers, whose mass-manufactured and standardized clothes allowed for the rise of Ivy.

The Shirt

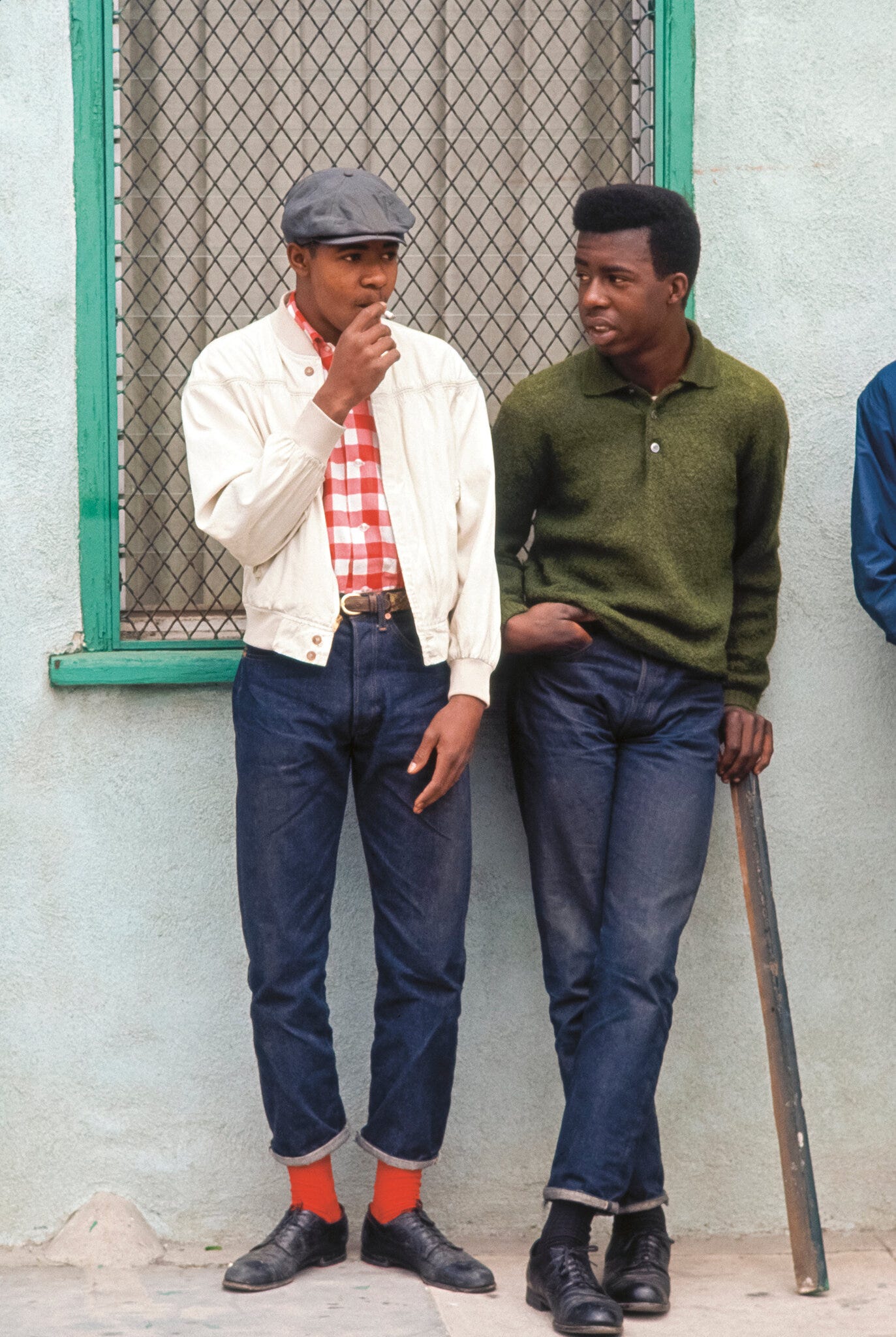

Being a short sleeve but collared shirt, my shirt is in between casualwear and formal wear, as is much of Ivy. Its bright colors and complex pattern is reminiscent of the peacock revolution, a subgenre of Ivy that was notable for its bright, flashy colors, or the flamingo shorts Truefelman mentioned in her podcast. Its lack of long sleeves like a traditional collared shirt allows for more movement and functionality, again something that was common among Ivy/athletic clothes. The shirt is undone to make it more casual while layered with another shirt, a defining characteristic of Ivy, like the image below.

The Pants

Khakis were adopted into the Ivy style after WWII when military members, taking their military clothes with them, began going to college. These shorts are akin to short versions of khakis, having a similar layout of pockets and materials but being blue instead of tan. Beings shorts, they are less restricting and formal than normal khakis, again a key characteristic of Ivy.

Works Cited

Trufelman, Avery. “American Ivy: Chapter 2.” Articles Of Interest, Articles Of Interest, 2 Nov. 2022, https://articlesofinterest.substack.com/p/american-ivy-chapter-2.

Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. “Sneakers Have Always Been Political Shoes.” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/12/sneakers-have-always-been-political-shoes/511628/. Accessed 5 March 2023.