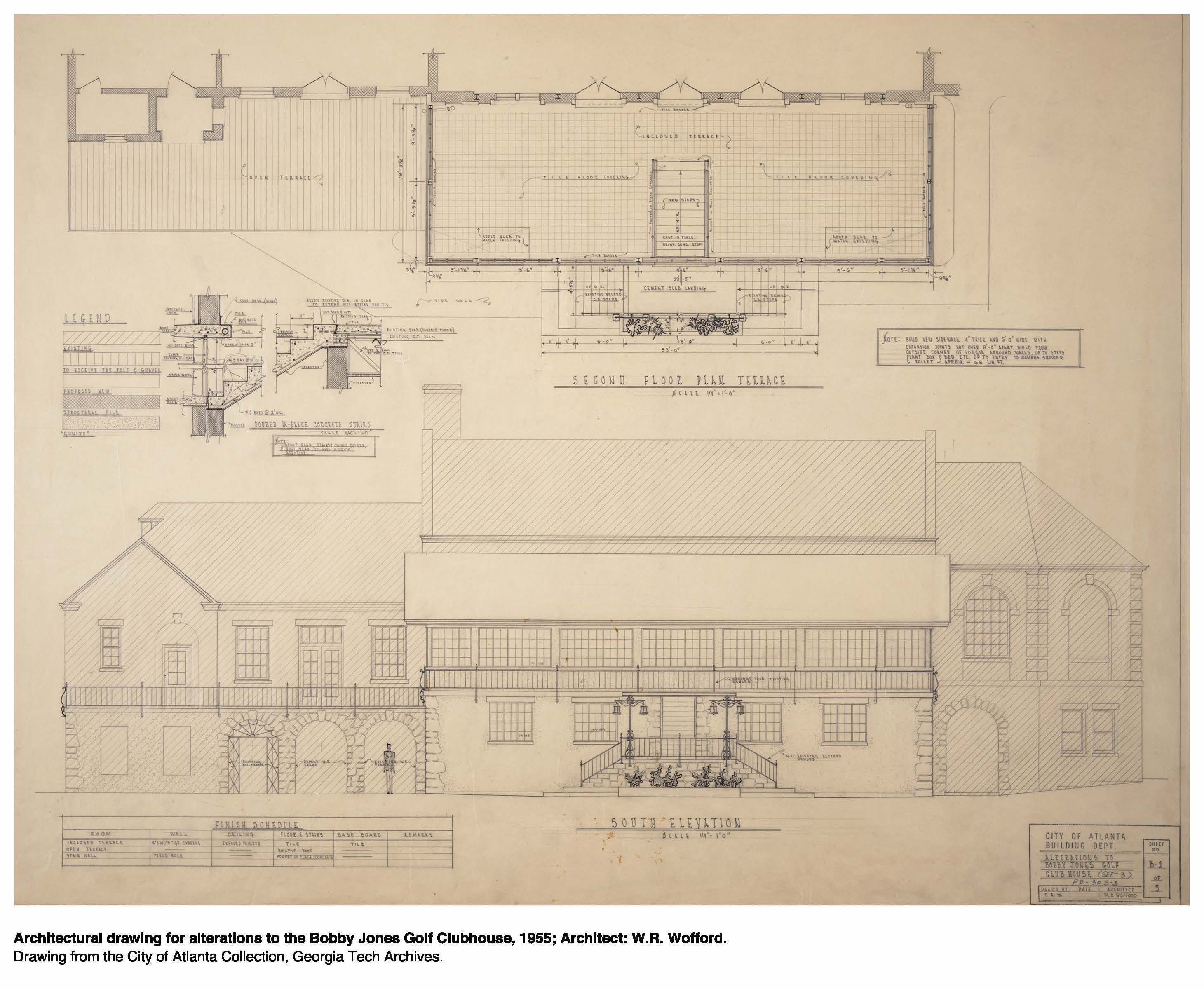

This drawing of Bobby Jones Golf Clubhouse was chosen for our archive because it demonstrates the painstaking detail that architects of the time would have to go into to make their completed drawings; one can see each line in the shading is perfectly straight and evenly spaced. The letters are so neatly penned, it looks like a font. There are five distinct shadings Wofford uses in his section view to represent the five different materials he uses, and they are all perfectly neat and distinguishable from one-another. The level of care is apparent to anyone looking at the drawing, and it gives the viewer a glimpse into the before-CAD era of architecture. Not only is this process extremely time-consuming and tedious (Nejadriahi), it is also not always easy for non-architects to fully understand what they are seeing. Parts of the drawing, like the “pour-in-place concrete stairs” on the left of the drawing, are very abstract-looking and heavily annotated. These sorts of drawings convey necessary information about the building, but it is not always easy for people to understand it simply by looking at the drawing. This separates the layperson from the process, as the architect from back then could not clearly communicate everything he or she wished to via pen-and-paper drawing. Recently, however, there have been developments in technology that laypeople closer to the design process by making it easier for the architect to show clients information about the building in new ways.

More recent developments in technology have given architects new tools with which to render their ideas; CAD, or “computer-aided design” has made it so simple pen and paper drawings are obsolete. Many CAD renderings are completely photorealistic. This rendering of the Kendeda building on Tech’s Campus is one such rendering.

The photo-realism of renderings like this not only allows for better communication between architect and client, it also gives the architect a much easier time. Making computer renderings is much more time-consuming than laboring over scale models or hand drawings, and this saves the architect from much tedious work, as well as making their ideas clearer to the client (Lawrence).

There have also been other developments in technology besides CAD; Geilman mentions in “How Technology is Revolutionizing the Architecture World” that architects now use virtual reality to allow clients to explore renderings as if they were walking through the halls of the building and visiting rooms. There have also been experiments in simulated architectural space- the Laboratory for Architectural Experimentation developed instruments to build the rooms and hallways of buildings they were designing with LEGO-like blocks so that the client could physically walk through the different floors of the building they wanted. A lot of the people who took part in these simulations said that they appreciated this new method of being shown architecture because most of them had trouble reading the sketch plans (Lawrence). Because architects have more effective tools to communicate their designs to their clients and people who may not be trained to read diagrams or schema, laypeople can get closer to the design process and be more involved in the input of the design.

A lot of improvements in technology has certainly improved the design process in many ways, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have drawbacks: some people believe that architects sometimes lean too much on computer programs, and the use of such programs in the early stages of the process might limit creativity or encourage poor design. The early stages of design do not require the precision that CAD provides, so many architects still prefer traditional methods like physical drawings and modeling because it allows for greater creative freedom (Nejadriahi). For example, in the above drawing of Bobby Jones Golf Clubhouse, Wofford had perfect creative freedom with how he drew the plans: the pattern of the stones surrounding the archways were drawn exactly how he envisioned them, and the lamppost in front of the building was hand-tailored to best fit the building’s aesthetic. In CAD, there are certain restrictions with the program that stint such creativity: perhaps only one style of lamppost exists in the program, or there’s less freedom with how cobblestones can be arranged on walls. Restrictions like these simply do not exist on pen and paper, and because of that, traditional methods of design allow for more complete creative freedom.