By: Arfa Ul-Haque

Title: Reynolds Pamphlet

Author: Alexander Hamilton

Date of Origin: August 25, 1797

Document originally found at “Founders Online” of the National Archives

Link: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-21-02-0138-0002

I owe perhaps to my friends an apology for condescending to give a public explanation.[1] A just pride with reluctance stoops to a formal vindication against so despicable a contrivance[2] and is inclined rather to oppose to it the uniform evidence of an upright character.[3] This would be my conduct on the present occasion,[4] did not the tale seem to derive a sanction from the names of three men of some weight and consequence in the society:[5] a circumstance, which I trust will excuse me for paying attention to a slander[6] that without this prop, would defeat itself by intrinsic circumstances of absurdity and malice.[7]

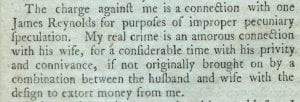

The charge against me is a connection with one James Reynolds for purposes of improper pecuniary speculation.[8] My real crime is an amorous connection with his wife, for a considerable time with his privity and connivance,[9] if not originally brought on by a combination between the husband and wife with the design to extort money from me.[10]

This confession is not made without a blush.[11] I cannot be the apologist of any vice because the ardour of passion may have made it mine.[12] I can never cease to condemn myself for the pang, which it may inflict in a bosom eminently intitled to all my gratitude, fidelity and love.[13] But that bosom will approve, that even at so great an expence,[14] I should effectually wipe away a more serious stain from a name, which it cherishes with no less elevation than tenderness.[15] The public too will I trust excuse the confession.[16] The necessity of it to my defence against a more heinous charge could alone have extorted from me so painful an indecorum.[17]

Before I proceed to an exhibition of the positive proof which repels the charge, I shall analize the documents from which it is deduced,[18] and I am mistaken if with discerning and candid minds more would be necessary.[19] But I desire to obviate the suspicions of the most suspicious.[20]

The first reflection which occurs on a perusal of the documents is that it is morally impossible[21] I should have been foolish as well as depraved enough to employ[22] so vile an instrument as Reynolds for such insignificant ends, as are indicated by different parts of the story itself.[23] My enemies to be sure have kindly pourtrayed me as another Chartres on the score of moral principle.[24] But they have been ever bountiful in ascribing to me talents. It has suited their purpose to exaggerate such as I may possess,[25] and to attribute to them an influence to which they are not intitled.[26] But the present accusation imputes to me as much folly as wickedness.[27] All the documents shew, and it is otherwise matter of notoriety, that Reynolds was an obscure, unimportant and profligate man.[28] Nothing could be more weak, because nothing could be more unsafe than to make use of such an instrument;[29] to use him too without any intermediate agent more worthy of confidence who might keep me out of sight,[30] to write him numerous letters recording the objects of the improper connection (for this is pretended and that the letters were afterwards burnt at my request) to unbosom myself to him with a prodigality of confidence,[31] by very unnecessarily telling him, as he alleges, of a connection in speculation between myself and Mr. Duer.[32] It is very extraordinary, if the head of the money department of a country, being unprincipled enough to sacrifice his trust and his integrity,[33] could not have contrived objects of profit sufficiently large to have engaged the co-operation of men of far greater importance than Reynolds, and with whom there could have been due safety,[34] and should have been driven to the necessity of unkennelling such a reptile to be the instrument of his cupidity.[35]

But, moreover, the scale of the concern with Reynolds, such as it is presented, is contemptibly narrow for a rapacious speculating secretary of the treasury.[36] Clingman, Reynolds and his wife were manifestly in very close confidence with each other.[37] It seems there was a free communication of secrets.[38] Yet in clubbing their different items of information as to the supplies of money which Reynolds received from me, what do they amount to?[39] Clingman states, that Mrs. Reynolds told him, that at a certain time her husband had received from me upwards of eleven hundred dollars.[40] A note is produced which shews that at one time fifty dollars were sent to him,[41] and another note is produced, by which and the information of Reynolds himself through Clingman,[42] it appears that at another time 300 dollars were asked and refused.[43] Another sum of 200 dollars is spoken of by Clingman as having been furnished to Reynolds at some other time.[44] What a scale of speculation is this for the head of a public treasury, for one who in the very publication that brings forward the charge[45] is represented as having procured to be funded at forty millions a debt which ought to have been discharged at ten or fifteen millions for the criminal purpose of enriching himself and his friends?[46]