Taiwan is the perfect case study when it comes to understanding how tropical cyclones interact with terrain. Taiwan is a small island nation east of China located in the most active tropical cyclone basin of the world. The island is only 250 miles in length but gets hit by 2-3 typhoons per year on average. Taiwan has the notorious reputation of being the “kryptonite” of typhoons because of how every storm seemingly disintegrates shortly after making landfall. It’s not surprising considering that the mountain ranges in Taiwan have a peak elevation of 12,000 feet.

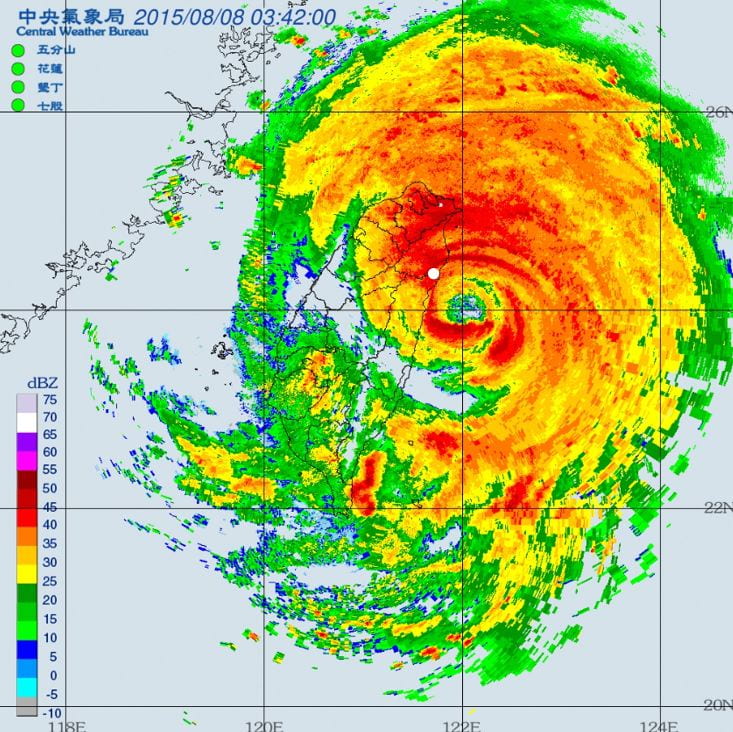

The following example below is Typhoon Soudelor (2015) which made landfall as a Category 3 equivalent with estimated 1-minute sustained winds of 115 mph. The center made landfall around 4:00 AM. A weather station that went through the northern eyewall (labeled as white dot) observed 10-minute sustained winds of 75 mph gusting up to 150 mph. The weather station also recorded minimum air pressure of 953 mbr which supports the satellite intensity estimation at the time. By 5:00 AM, the eye had collapsed and was no longer visible on both radar and satellite imagery.

(Source: https://rdc28.cwb.gov.tw/TDB/public/typhoon_detail?typhoon_id=201617)

Surface wind observations along the west coast were much lower. The strongest winds occurred in Chiayi city (labeled as white dot) where the center passed 20 miles north. The station observed 10-minute sustained winds of 31 mph gusting to 76 mph with a minimum pressure of 963 mbr. Although the central pressure has not risen significantly, the surface wind observations do imply significant weakening due to the mountain terrain.

(Source: https://rdc28.cwb.gov.tw/TDB/public/typhoon_detail?typhoon_id=201617)

It’s also evident from the radar imagery that there’s a large difference in precipitation between the windward and leeward side of the Typhoon. As the storm nears landfall, the wind direction north of the center will be from the east. Precipitation will be concentrated toward the northeast quadrant of the island. The south side of the storm receives little to no precipitation because most of the moisture wrapping around from the northeast is blocked by the central mountain ranges. The dry westerly winds from the typhoon and steep terrain create the perfect condition for foehn wind in the southeast quadrant of the island. The figure below is the observation data of Taitung city which was located approximately 100 miles south of the landfall location. The data reveals a temperature spike from 27c to 36c once the wind direction shifted from N to SW around the time of landfall.

(Source: https://rdc28.cwb.gov.tw/TDB/public/typhoon_detail?typhoon_id=201617)

The dynamic reverses once the center crosses the mountain range. The southwest quadrant of the island is now on the windward side and receives the bulk of the precipitation. Sometimes the typhoon can amplify the southwesterly monsoonal flow. The moisture colliding with mountains can potentially dump significant amounts of rain. Typhoon Morakot (2009) for example dumped 112 inches of rain in southern Taiwan which caused massive landslides that wiped out villages and killed hundreds.

Terrain can often influence the track of Typhoons. It’s not uncommon to see Typhoons near landfall wobble outside of the cone of probability. In cases of weak steering currents, a slow-moving Typhoon can fail to cross the mountain range and stall which was the case for Typhoon Saola in 2012. It eventually retreated offshore and looped around the northern coastline of Taiwan as shown in the figure below.

(Source: https://rdc28.cwb.gov.tw/TDB/public/typhoon_detail?typhoon_id=201209)

Typhoons that make landfall in central Taiwan usually deviate south after landfall toward the narrowest part of the mountain range. Once the center has crossed, it recorrects north to its original trajectory. Notable examples include Typhoon Soudelor 2015 (Fig 2), Typhoon Dujuan 2015, and Typhoon Megi 2016.

(Source: https://rdc28.cwb.gov.tw/TDB/public/typhoon_detail?typhoon_id=201617)