Figure 1: National Reflectivity Mosaic on March 30, 2022 at 18 UTC. A strong, tight squall line over central Louisiana is marching its way eastward. The heavier precipitation is colorized in red and lighter precipitation is colorized in green (measured in dBz). (Source: ncei.noaa.gov)

Figure 2: WPC Surface Analysis w/ surface fronts on March 30, 2022 at 18 UTC. Red numbers: Temperature, Green numbers: Dew Point, Wind direction depicted by barbs with speed attached, and types of weather in pink. Brown lines: Height Contours. Underlined numbers: dominate pressure associated with high and low pressures.

On March 30th of 2022, the southeast was in route for yet another round of potentially dangerous weather with a 992 mb mid-latitude cyclone positioned over southwest Wisconsin (Figure 2). A strong squall line began to march over from Texas/Oklahoma where it began to increase in strength (Figure 1). With this squall line came heavy rain, gusty winds, and tornadoes. This area was enhanced by the strong moisture flow from the Gulf of Mexico as denoted by the dewpoints ahead of the cold front (Figure 2).

Figure 3: Airmass RGB image of CONUS on March 30, 2022 between 18 and 19 UTC. The description of each color is provided by the color scale at the bottom of the image. (Source: rammb-slider.cira.colostate.edu)

The cold front that is positioned over CONUS (Figure 1) and its characteristics can be shown through an Airmass RGB image (Figure 3). The warm moist air depicted in green is providing moisture into the warm sector of this advancing cold front. Behind the cold front, dry, cold air is advancing and causing a dry line identified by the drastic changes of dew points (Figure 1). These events are essential for tornadic activity. The beautiful image of the squall line as well as the cloud formations to the north are both highlighted in white. Overtime, you can see strong convective activity over Louisiana, illustrated by the “popping” of clouds. The jet steam can be identified by the red area. By viewing this image, we can note there is trough over the Northeastern border of Texas, as well as a ridge reaching up to the border of the United States and Canada. To verify the jet stream location, we can look at a 250 mb map (Figure 4). By following the strongest wind speeds across CONUS between 40 – 50 m/s, a jet stream can be identified which exists over central CONUS. The strongest storms are to the right of the trough located in Louisiana.

Figure 4: 250mb map on March 30, 2022 at 18 UTC that shows higher wind speeds in pink (m/s). Sea level pressure is given in black counters every 4 mb. 1000-500 thickness countours are shown in the dashed red and blue countours every 6 meters. (Source: Alicia Bentley)

The atmosphere over the Louisiana is dynamically unstable given the effective bulk shear values present (Figure 5). Effective bulk shear is necessary for vertical rotation within a column of air. At 18 UTC, an area of 60 kt effective bulk shear is present that promotes the rapid development of supercells. Typically, anything larger than 40 kts worth of effective bulk shear has the potential to create supercells and tornadoes. Additionally, the atmosphere is moderately unstable regarding the thermodynamics considering the 2,000 J/kg reading of CAPE, or Convective Available Potential Energy, which represents the energy in the atmosphere where parcels can be lifted to its level of free convection (Figure 6). This is more than enough CAPE to help produce severe weather capable of producing tornadoes.

Figure 5: March 30, 2022 at 18 UTC – Effective Bulk Shear given in knots over the southern U.S. (Source: spc.noaa.gov)

Figure 6: March 30, 2022 at 18 UTC Surface-Based CAPE given in J/kg over CONUS colored with red contours. CIN is shaded in 25 and 100 in light/dark blue (Source: spc.noaa.gov)

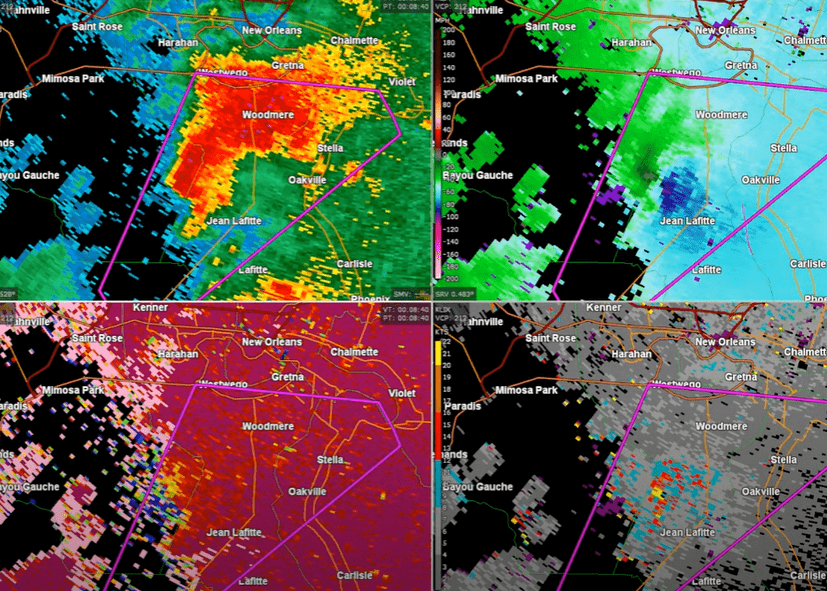

The storm reports on 3/30/22 had an astounding 69 tornado reports, 291 wind reports, and 2 hail reports (Figure 7). The main section of severe storms I highlighted were in the northeast Louisiana area, but as this system continued to move eastward, Mississippi and Alabama were hit with a huge tornado outbreak. For my synoptic/mesoscale verification, there were approximately 8 tornadoes to hit the Louisiana area. Thankfully, no injuries were reported with any of the tornadoes. Downed power lines and uprooted trees sustained the bulk of the damage.

Figure 7: March 30, 2022 SPC Storm Report with tornado reports colored in red, wind reports in blue, and hail reports in green. (Source: spc.noaa.gov)