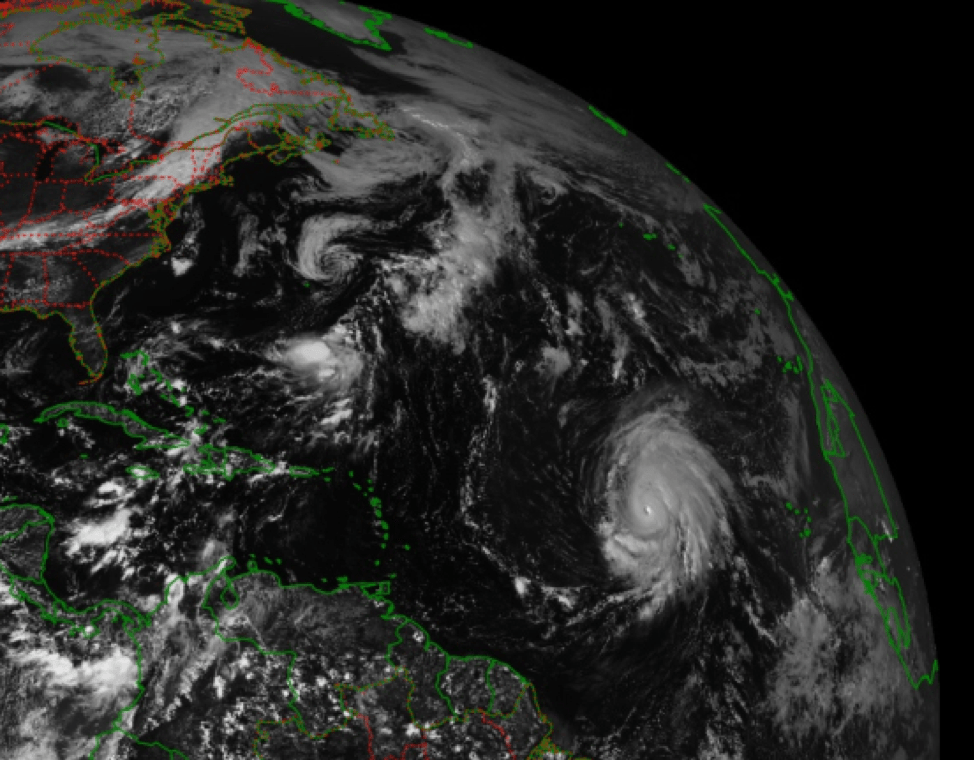

While the United States has had some tropical storm events happen closer to home, there’s now a formidable cyclone building in the mid-Atlantic, and its name is Lorenzo. On September 26, 2019, Lorenzo is classified as a category 3 hurricane, and expected to strengthen to category 4 in the near future. Fortunately for readers, Lorenzo is not expected to reach the United States as a hurricane, or any other landmass. Even if Lorenzo doesn’t make landfall, it is a great opportunity to observe hurricane formation unimpeded by landmasses. The eye is particularly striking in Figure 1, standing out from the cloud outflow surrounding it due to the angle of the Sun at the time of viewing.

Fig. 1. GOES-16 full disc visible imagery with Lorenzo west of the African coast, taken 26 September 2019 at 17:20 GMT (or 1:20 PM EDT).

Lorenzo is projected to become a category 4 hurricane, but it’s also likely to be demoted back to a category 3 soon after. Taking a look at the Airmass RGB data from GOES-16 and Meteosat may help answer why – green regions represents moist, tropical airmasses and rusty orange regions represent dry airmasses, and Lorenzo’s got a dry orange region similar in size to itself just to its west (Fig. 2). I’ve taken imagery from two satellites in this case because Airmass RGB tends to wrap the horizon with a blue/purple hue due to how it detects water vapor. If Lorenzo continues west, it will have to interact with the dry air region, which could weaken its development by halting moisture intake. If Lorenzo moves north, it will have to contend with cooler water temperatures that could also weaken its development, as colder seawater will evaporate less readily.

Fig. 2. GOES-16 (left) and Meteosat 0 degree (right) full disc Airmass RGB composite imagery of Lorenzo taken 26 September 2019 at 21:00 GMT (or 5 PM EDT).

The good news is that Lorenzo in its current form likely won’t directly impact continental landmasses. The bad news (for Lorenzo) is its possible trajectories all lead to a weakening system in the near future. Incidentally, the dry air region to Lorenzo’s west could be a fragment of the Saharan Air Layer, a hot and dry airmass that advects out of the Sahara during the warmer months. The SAL isn’t always loaded with dust, but it often is, and some dust particles on Dust RGB imagery can be seen to the west of Africa at the time of this post (Fig. 3). We could have Africa to thank for stopping Lorenzo from getting out of control!

Fig. 3. Meteosat 0 degree Dust RGB over Africa, taken 26 September 2019 at 18:00 GMT. Dust is represented in pink hues.

GOES-16 full disc visible imagery can be found at https://whirlwind.aos.wisc.edu/~wxp/goes16/vis/goes16_fulldisk.html

GOES-16 full disc Airmass RGB imagery can be found at https://whirlwind.aos.wisc.edu/~wxp/goes16/multi_air_mass_rgb/goes16_fulldisk.html

Meteosat full disc Airmass RGB imagery can be found at https://eumetview.eumetsat.int/static-images/MSG/RGB/AIRMASS/FULLDISC/index.htm

Meteosat full disc Dust RGB imagery can be found at https://eumetview.eumetsat.int/static-images/MSG/RGB/DUST/FULLRESOLUTION/